Version control vocabulary

There is a lot of vocabulary involved in working with Git, and often the understanding of one word relies on your understanding of a different Git concept. Take some time to familiarize yourself with the words below and read over it a few times to see how the concepts relate.

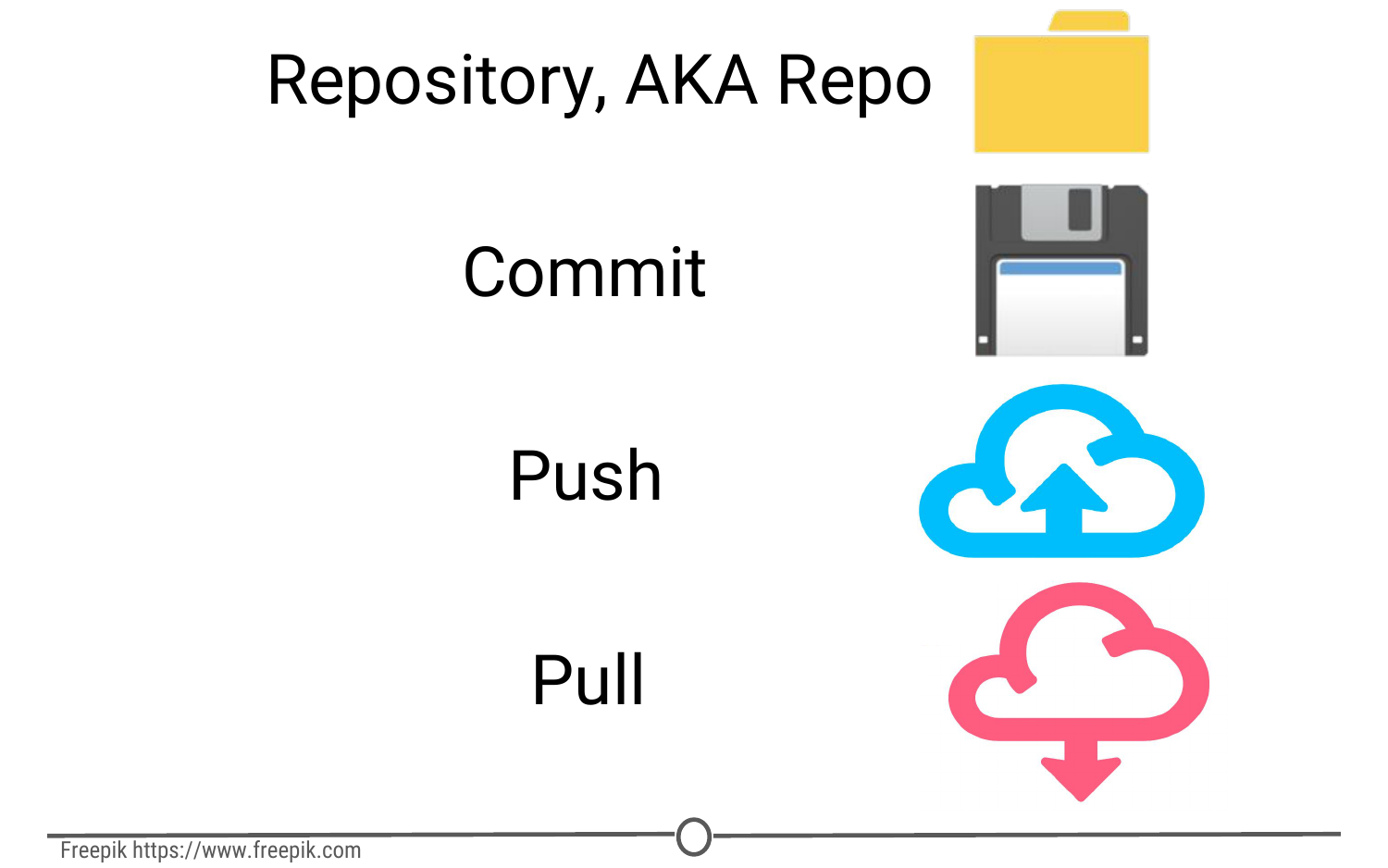

Repository:

Equivalent to the project’s folder/directory - all of your version controlled files (and the recorded changes) are located in a repository. This is often shortened to repo. Repositories are what are hosted on GitHub and through this interface you can either keep your repositories private and share them with select collaborators, or you can make them public - anybody can see your files and their history.

Commit:

To commit is to save your edits and the changes made. A commit is like a snapshot of your files: Git compares the previous version of all of your files in the repo to the current version and identifies those that have changed since then. Those that have not changed, it maintains that previously stored file, untouched. Those that have changed, it compares the files, logs the changes and uploads the new version of your file. We’ll touch on this in the next section, but when you commit a file, typically you accompany that file change with a little note about what you changed and why.

When we talk about version control systems, commits are at the heart of them. If you find a mistake, you revert your files to a previous commit. If you want to see what has changed in a file over time, you compare the commits and look at the messages to see why and who.

Push:

Updating the repository with your edits. Since Git involves making changes locally, you need to be able to share your changes with the common, online repository. Pushing is sending those committed changes to that repository, so now everybody has access to your edits.

Pull:

Updating your local version of the repository to the current version, since others may have edited in the meanwhile. Because the shared repository is hosted online and any of your collaborators (or even yourself on a different computer!) could have made changes to the files and then pushed them to the shared repository, you are behind the times! The files you have locally on your computer may be outdated, so you pull to check if you are up to date with the main repository.

Analogies to these concepts

Staging:

The act of preparing a file for a commit. For example, if since your last commit you have edited three files for completely different reasons, you don’t want to commit all of the changes in one go; your message on why you are making the commit and what has changed will be complicated since three files have been changed for different reasons. So instead, you can stage just one of the files and prepare it for committing. Once you’ve committed that file, you can stage the second file and commit it. And so on. Staging allows you to separate out file changes into separate commits. Very helpful!

To summarize these commonly used terms so far and to test whether you’ve got the hang of this, files are hosted in a repository that is shared online with collaborators. You pull the repository’s contents so that you have a local copy of the files that you can edit. Once you are happy with your changes to a file, you stage the file and then commit it. You push this commit to the shared repository. This uploads your new file and all of the changes and is accompanied by a message explaining what changed, why and by whom.

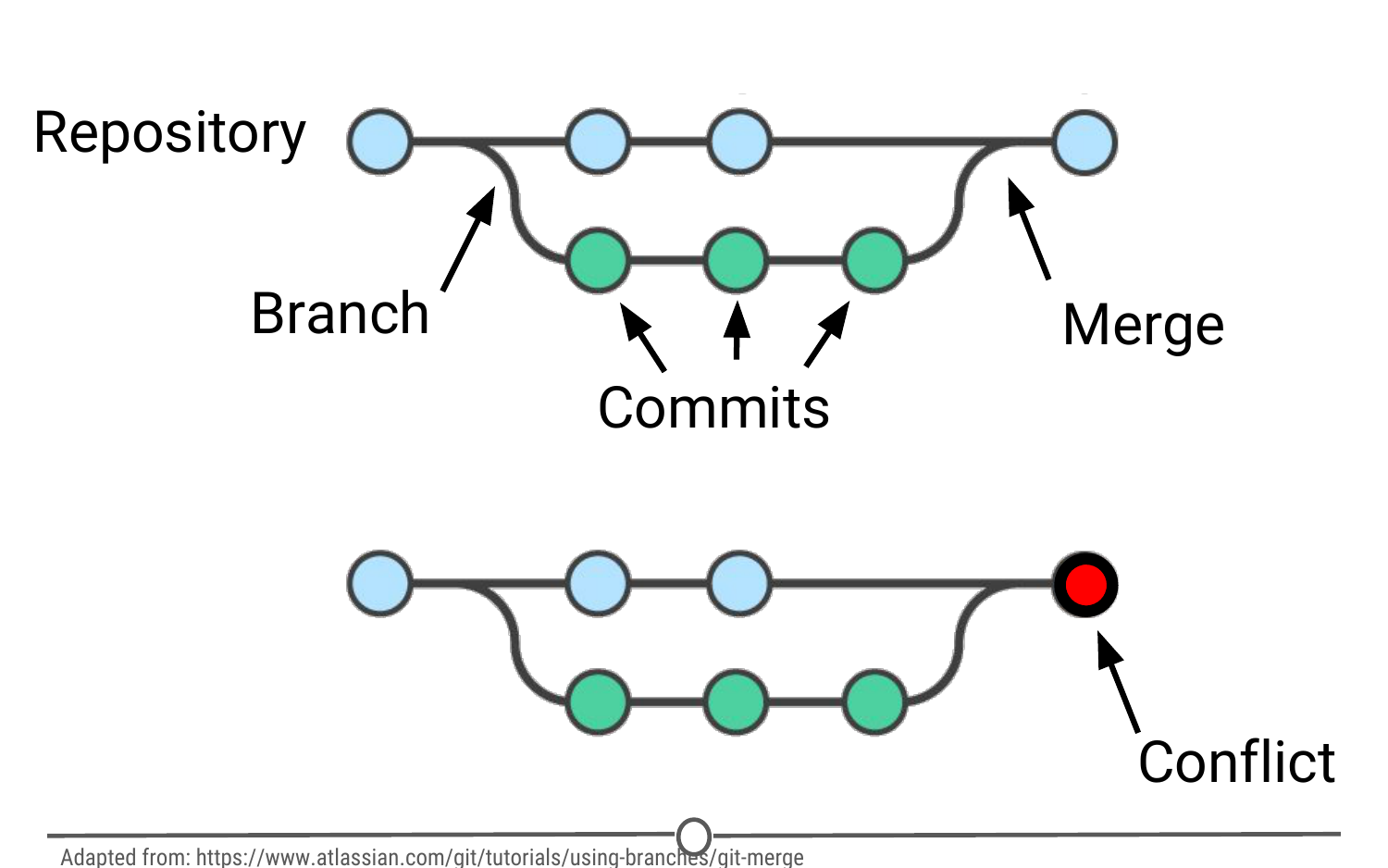

Branch:

When the same file has two simultaneous copies. When you are working locally and editing a file, you have created a branch where your edits are not shared with the main repository (yet) - so there are two versions of the file: the version that everybody has access to on the repository and your local edited version of the file. Until you push your changes and merge them back into the main repository, you are working on a branch. Following a branch point, the version history splits into two and tracks the independent changes made to both the original file in the repository that others may be editing, and tracking your changes on your branch, and then merges the files together.

Merge:

Independent edits of the same file are incorporated into a single, unified file. Independent edits are identified by Git and are brought together into a single file, with both sets of edits incorporated. But, you can see a potential problem here - if both people made an edit to the same sentence that precludes one of the edits from being possible, we have a problem! Git recognizes this disparity (conflict) and asks for user assistance in picking which edit to keep.

Conflict:

When multiple people make changes to the same file and Git is unable to merge the edits. You are presented with the option to manually try and merge the edits or to keep one edit over the other.

A visual representation of these concepts, from https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/using-branches/git-merge

Clone:

Making a copy of an existing Git repository. If you have just been brought on to a project that has been tracked with version control, you would clone the repository to get access to and create a local version of all of the repository’s files and all of the tracked changes.

Fork:

A personal copy of a repository that you have taken from another person. If somebody is working on a cool project and you want to play around with it, you can fork their repository and then when you make changes, the edits are logged on your repository, not theirs.

Best practices

It can take some time to get used to working with version control software like Git, but there are a few things to keep in mind to help establish good habits that will help you out in the future.

One of those things is to make purposeful commits. Each commit should only address a single issue. This way if you need to identify when you changed a certain line of code, there is only one place to look to identify the change and you can easily see how to revert the code.

Similarly, making sure you write informative messages on each commit is a helpful habit to get into. If each message is precise in what was being changed, anybody can examine the committed file and identify the purpose for your change. Additionally, if you are looking for a specific edit you made in the past, you can easily scan through all of your commits to identify those changes related to the desired edit.

You don’t want to get in the same habit that XKCD has!

Finally, be cognizant of the version of files you are working on. Frequently check that you are up to date with the current repo by frequently pulling. Additionally, don’t horde your edited files - once you have committed your files (and written that helpful message!), you should push those changes to the common repository. If you are done editing a section of code and are planning on moving on to an unrelated problem, you need to share that edit with your collaborators!

A summary of the main best practices to keep in mind as you work with version control

Summary

Now that we’ve covered what version control is and some of the benefits, you should be able to understand why we have three whole lessons dedicated to version control and installing it. We looked at what Git and GitHub are, and then covered much of the commonly used (and sometimes confusing!) vocabulary inherent to version control work. We then quickly went over some best practices to using Git – but the best way to get a hang of this all is to use it! Hopefully you feel like you have a better handle on how Git works than the people in this XKCD comic ! So let’s move on to the next lesson and get it installed!